Executor of Estate: The Complete Guide

30 Min Read | Jul 24, 2024

Depending on your taste in television, executor of estate may sound like the head butler on Downton Abbey or a possible pro wrestler name. But either way, there’s nothing fictional about this important legal role. An executor of estate is the person appointed in a will to make sure the deceased’s wishes are met.

Maybe you’ve been asked to serve as the executor for a friend or family member, and you’re wondering how it all works. Or you might be researching how to make a will for yourself and wondering how to choose the best person as an executor for your own estate. Just keep reading and we’ll walk you through how this whole thing works.

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways

- An executor of estate is the person who makes sure the deceased’s will gets carried out.

- An executor’s responsibilities include filing the will, starting the probate process, telling everyone about the death, figuring out what and where all the assets are, paying taxes, and handing out the inheritances to beneficiaries.

- Being an executor comes with a lot of potential complications. Executors often have to deal with disputes, work with co-executors, and commit a lot of time to the process.

- Executors do get paid.

What Is an Executor of Estate?

An executor of estate makes sure a will gets executed, or carried out—hence the name. (And if you didn’t know, an estate just means somebody’s stuff and money.) They’re the person who’s either named in the will by the person who wrote the will or by a court of law.

If you take this role on for someone with a will, you’ll have several responsibilities:

- Getting the deceased’s assets to the beneficiaries (otherwise known as passing out their stuff as described in the will)

- Passing on any wishes from the letter of instruction

- Paying off debts

- Filing final tax returns for the deceased (the person who wrote the will in the first place)

- Notifying the Department of Health in the deceased’s state of residence about the death of the testator (another name for the person who wrote the will)

While it’s not as fun as ordering around servants or body slamming some guy, it’s pretty obvious an executor of an estate does have to wrestle through a lot of instructions and tell a few people what to do. And most of the duties revolve around money, so it’s not a responsibility to take on lightly. Anyone who becomes an executor of estate is required by law to do all in their power to protect the estate’s assets, sometimes known as fiduciary duty.

If you’re tapped for the job of executor, try to see it as an honor. Yes, it’s a challenging role, but executors are chosen because they’re responsible, honest, diligent and impartial people. Those are some pretty noble qualities!

So, how do people wind up in such a role? Let’s see.

How Is an Executor of Estate Appointed?

Whether someone dies with a will stating who should fill the role or not, an executor must be approved and appointed by a probate judge.

FYI: Anytime someone dies, it sets in motion a legal process called probate. The purpose of probate is to make sure the departed’s property and possessions go to the correct people, and any remaining taxes or debts owed get paid. If the person dies with a valid will in place, the process is a lot easier for everyone. If they don’t, things get more complicated.

Regardless, a probate judge determines who should act as the executor of estate.

Here’s what that looks like:

1. Find out if there’s a will.

If the person who died had a will and it names an executor for the estate, the search for an executor might already be over—but there are some conditions to that . . .

2. Confirm the will is valid.

Let’s say the will checks out, it actually names an executor, and the judge confirms it’s valid. The next step is confirming that person for the job (outlined in step 3).

Save 10% on your will with the RAMSEY10 promo code.

But that’s the best-case scenario. It could turn out the will gets ruled invalid because it wasn’t properly witnessed or notarized, or it doesn’t comply with certain state laws. In those cases, the judge will have to keep looking, and will likely skip to step 5 below. On the other hand, it could be ruled a valid will, but the judge could find that it fails to name an executor. They’ll once again skip to step 5 below.

3. Verify that the executor named in the will is eligible.

The judge might have to override the testator’s choice of an executor for a few different reasons. A named executor can be passed over if:

- They’re still underage at the time of probate.

- They have a mental disability.

- They have a criminal record.

- They have a history of substance abuse.

- They’re dead.

If the named executor passes each of those tests, you’d think you’d surely pinpointed the right person for the job. But wait! You can’t assume they’re willing to do it.

4. Find out whether the person named in the will wants the job.

The court can’t force anyone to take on the job of executor of estate. It’s a time-consuming project, and it can potentially involve financial risk.

Even though it’s customary to compensate anyone taking it on with pay from the estate itself (if there’s anything left), the person named may just not have the time or inclination. So, the court has to find out whether the person named is up for it. If the probate judge confirms the person named is willing to serve, the search for an executor is over! If they’re not? Proceed to step 5.

5. Appoint someone as an estate administrator.

In situations where the judge can’t decide on a legal executor of estate through a will, they’ll appoint someone to the job, usually a close relative. (In the case of a will that was overruled on a technicality, the judge could still choose the original executor to serve.) Their formal legal title becomes estate administrator or personal representative, but those are just other names for executor.

Can Someone File to Be Executor of an Estate Without a Will?

If the deceased died without a will, the job of executor of their estate is open. And if you feel like you could do a good job and want to take it on, you can apply to the court for the job. Read through all an executor of estate’s duties, though, and make sure you’re up for it.

Also, check the laws in your state around dying intestate (legal lingo for dying without a will). States have rules around who the court usually appoints as default executor. Most often, any spouse or adult children are considered first for the job. If you’re a friend or sibling, you have to get their permission to be executor. So check with those folks first to make sure they’re okay with you being appointed.

Maybe the decedent talked to you about being executor while they were alive but never wrote it down in their will. This could actually influence the court in your favor over people who usually have more priority. Still, it’s a good idea to talk with those people and get them on board. Otherwise, you could be in for some fights that make the Real Housewives of Wherever look like a children’s show.

To actually put your name forward for executor, you’ll have to communicate with the probate court to find out filing requirements and deadlines. You then need to file all the appropriate forms and documents. You may even be required to put some money on the line (called a probate bond) to ensure you carry out your duties and protect the estate financially in case you mess something up.

Other Common Terms for Executor

An executor by any other name would smell as official. Well, maybe not any other name. If we called them roses, for instance, it might get confusing. But there are a couple other names you might run into for executor.

Personal representative: In some states, this is what executors are called. But your job is the same.

Executrix: Yes, you read that right. And no, it’s not another Harry Potter character. This is an old-fashioned term for female executor. It’s pretty outdated, but wills can be old, so it’s good to be familiar with it.

Agent: Have you ever wanted a cool name like Agent 007? Well, now you can be Agent Brian—or whatever your name is. It doesn’t come with a license to kill or anything like that (despite the term executor), but you can still brag to your friends that you were an agent.

Administrator: An executor can be called the will’s administrator. We’d stick with agent though because it’s way cooler.

Fiduciary: Sometimes you might hear an executor referred to as a fiduciary. It’s true that an executor is a fiduciary, but a fiduciary isn’t always an executor. Fiduciary is a more general term for someone (or some entity) that you entrust to manage your property (it can include trustees).

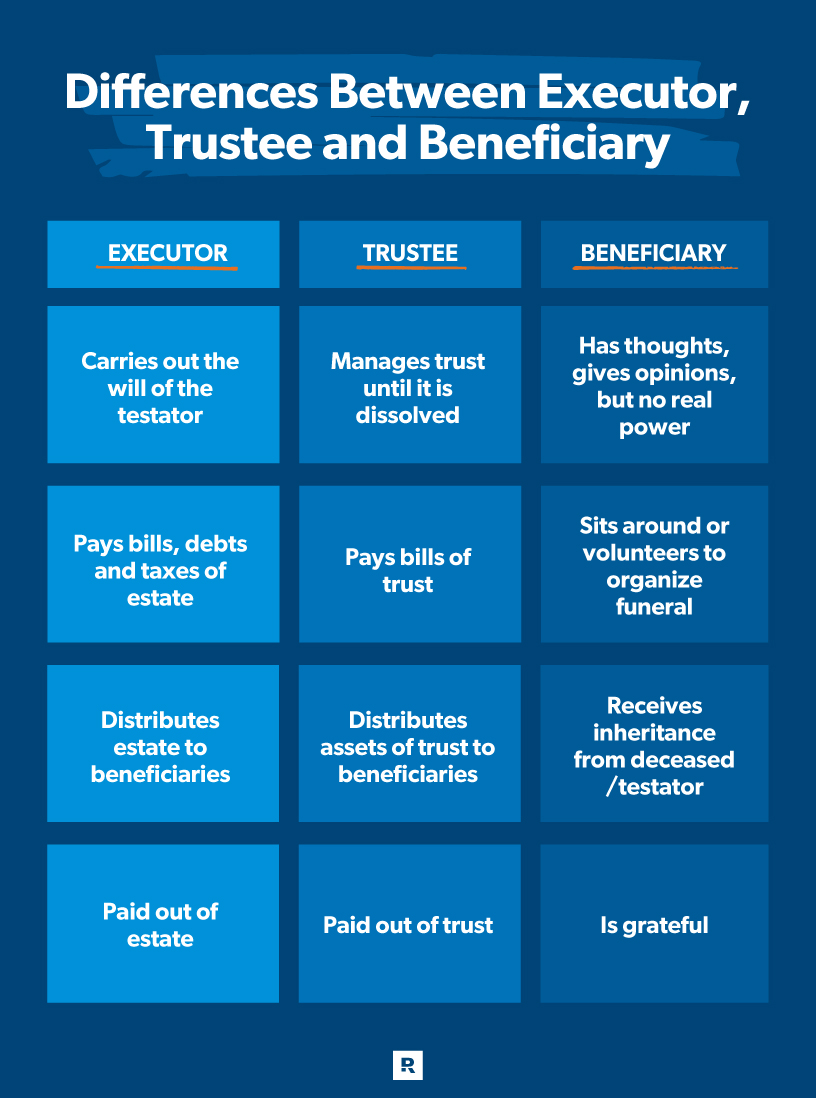

How Is an Executor Different From a Trustee?

The big difference between an executor and trustee is one deals with a will while the other administers a trust. Can you guess which? Sometimes the deceased has both a will and a trust. In that case, the executor and the trustee can technically be the same person, but keep in mind they’re fulfilling different roles.

What Are the Limitations of the Executor of Estate?

It’s an executor’s duty to do everything in the best interest of the estate they represent. An executor of estate definitely cannot do anything that would knowingly:

- Delay or prevent the payment of estate debts

- Get the estate mixed up in tax evasion

- Keep beneficiaries from receiving what they’re supposed to get

Being executor comes with a lot of power, which is another reason why the person taking it on must be trustworthy. They certainly can’t do anything for personal gain, like cutting themselves a massive check for being executor that uses up so much of the estate’s money there’s almost nothing left. That’s pretty low-down, and anyone who tried it would end up in trouble with the law for being a negligent executor.

No executor worth the name will refuse to pay legit creditors or hold back payments to beneficiaries as laid out in the will. For a lot of executors, a big part of their job is putting the deceased’s property up for sale so they can use that money to settle debts or pay beneficiaries. Executors are expected to get an outside opinion on how to price the assets to make sure they’re sold for a fair market price.

Another no-no? Something known as self-dealing, where an executor tries to pull a fast one for a huge financial gain. For example, taking advantage of what you know about the deceased’s home to purchase it for way under market value and then living in it yourself.

An executor of estate needs to have a servant’s heart. There are a number of details they’ll need to keep in mind as they go about the business of settling the decedent’s estate. But an executor’s first goal should be to steer clear of legal troubles—both for their own sake and that of the estate and its beneficiaries.

Can an Executor Also Be a Beneficiary?

It’s quite common for an executor to be a beneficiary also—parents often name one of their kids, for example. This works well when family dynamics are healthy, but knives could come out if the beneficiaries involved don’t get along or are unhappy about the choice.

If you’re thinking about who to name as an executor in your will and your family isn’t the most harmonious bunch, consider naming a neutral party like a bank to execute the estate.

Executors who are also beneficiaries often waive their payment because it comes out of the estate and is taxable, while an inheritance is not.

If you’re writing your will and naming one of your beneficiaries as executor, consider allocating extra assets to them in their inheritance. That way they can be compensated for their trouble while avoiding the tax associated with payment.

What Are the Executor of Estate’s Responsibilities?

There are quite a few things an executor of estate needs to be aware of going into their duties. Here we go!

File the will.

Yeah, don’t miss this all-important first step. We know the death of a friend or relative is hard, but it’s the executor’s job to quickly file both the will and the death certificate with the local health department and the local probate court. In some states, you have a month. In others, it must be done within a few days of the death.

Start the probate process.

You can probably do this the same day you file the will with the probate court.

If the idea of going to court scares the chocolate yogurt out of you, relax. Probate court is usually just sitting around a table with a judge (and maybe your lawyer) and signing a few papers. Super chill.

To get the ball rolling, the court will issue you a document known as letters testamentary that confirms your legal rights as the executor of estate. Although the question of which kinds of assets are required to go through probate varies by state, it’s always up to the executor to find out the laws where they live. Typically, the following kinds of assets don’t require probate:

- Life insurance policies

- Bank accounts

- Other payable-on-death accounts that allow you to name beneficiaries for those specific accounts—like a 401(k) or IRA

Tell everyone who needs to know about the death.

Here’s a list of who you’ll be responsible for notifying about the death:

- Beneficiaries listed in the will

- Local media, for the purpose of posting an obituary

- Family and blood relatives who could have a legal claim on the deceased’s property

- Creditors who may be owed money by the estate

- Insurance companies

- Guardians of minors

- The Social Security Administration

- Medicare, if applicable

- The Department of Veterans Affairs, if applicable

- Banks and other financial institutions

- The U.S. Postal Service

Start a bank account for the estate.

As an executor, a big part of your job is paying people—debts, taxes and beneficiaries. To protect yourself and keep everything legal and aboveboard, open a bank account specifically for conducting estate business.

Figure out what (and where) all the assets are.

Since your responsibility as executor is to deliver every cent and asset to its new legal home, your first task is to locate all the deceased’s important documents, account details and actual stuff—and make sure it’s safe.

Don’t let anyone physically remove stuff from the decedent’s estate until you as the executor have determined who it truly belongs to. So nobody should be carrying away their dearly departed Aunt Agatha’s pearls, not even her niece who promises you she was always Aunt Agatha’s favorite. For all you know, those pearls belong to Cousin Cleo in Cleveland. If you let them out of your sight, you could be on the hook for a pretty pearl . . . err, penny!

Don’t forget about larger property either (we’re talking dirt). Did the deceased have a mortgaged house or piece of land? You’ll need to make sure payments keep going out on time until the land is sold or given to a beneficiary. You’ll also need to keep up with rental properties, including collecting rent or listing them for sale (or both). And be sure to let the probate court know if you take any of these actions.

Cover taxes and debts.

Death and taxes are the only things in life you can be sure of, according to ol’ Ben Franklin. Well, death immediately followed by taxes is also a very reliable scenario.

Make sure you take care of the deceased’s taxes and pay off any debts—and do it in that order.

- Find out if the deceased still owed taxes and file income taxes for the estate return (Form 1041) if necessary.

- Large estates may have to pay federal estate taxes, and it’s up to the executor to make that payment from the estate’s assets.

It’s very important the executor pays federal taxes out of the estate before paying out anybody else—including creditors and beneficiaries. If they pay out in the wrong order and run out of money, the executor can be held responsible for taxes owed and have to pay out of their own pocket. If tax season isn’t coming up any time soon, set aside what you expect to pay in taxes and then move on with the rest.

Give the assets to their beneficiaries.

Now we get to the best part! Especially if you know and love the beneficiaries, making sure they receive their inheritance can be a real treat, and an honor!

Now that you’ve taken care of the death and taxes part (and confirmed with the probate court that all tax and debt obligations are fulfilled), you can get down to the business of honoring the decedent by making sure everyone they loved gets what’s intended for them.

Have fun handing out the money and stuff to friends and family!

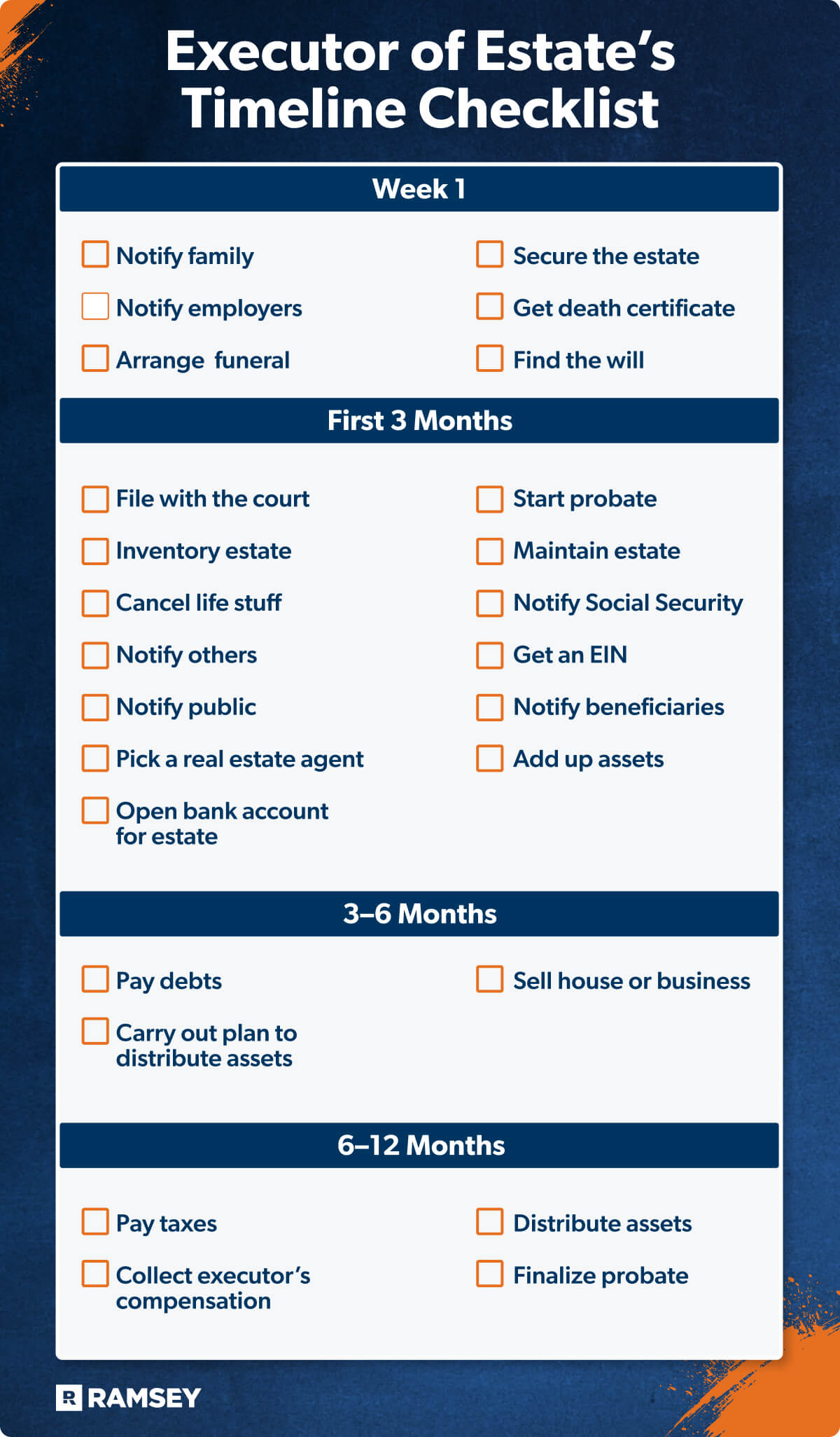

When Do the Executor of Estate’s Duties Begin, and What Is the Timeline?

Estates can take anywhere from six to 18 months to settle, and the executor is involved at every step along the way (yeah, we weren’t kidding when we said it’s a big job). Here’s a rough timeline of what you can expect to do when executor of estate.

Week 1

The week immediately following the person’s death is full of practical duties.

Notify the family. One of the first things you’ll do is notify family and close friends about the death.

Notify any employers. If the decedent had a job, make sure the employer knows.

Secure the estate. This means . . . lock the doors on the house. Make sure any valuables are in a safe place. Grab the mail regularly. Cancel any subscriptions or services, like housekeeping or meals. Arrange for pet care and lawn care if necessary.

Arrange the funeral. While this isn’t a legal responsibility of the executor, it may fall to you to organize and delegate decisions about the deceased’s funeral service. If someone else is willing to take this responsibility, it’s probably a good idea to let them take over this job. You’ll have plenty of other tasks on your plate.

Get the death certificate. Make sure to get at least two copies of the death certificate from either the funeral home, crematorium, or state vital records office. One copy is for using immediately and the other is backup. Heads up: You can’t file for probate or pay any bills without a death certificate, so don’t wait to get your copies!

Find the will. You’ll also need to figure out where the will is. Hopefully, the decedent gave you access to a copy (like in a legacy drawer) and told you where to find the original. But if they didn’t, there are a few places you can check. Ask any personal lawyer the decedent had, check their safety deposit box, and check the court or register of authorized wills if your state has one.

First 3 Months

This is when you really start digging into the technical stuff.

File the will with the court. Get that will to the court! States differ on how long you have, but some give as little as 10 days to submit the will. This is also a good time to decide if you need a lawyer. Take a look at the will and estate—if it looks tricky, you might want a lawyer’s help. They’re expensive, but they can be really helpful with a lot of the legwork.

Notify the beneficiaries of the probate hearing. This won’t be fun—not that anything else we’ve listed so far is a barrel of laughs. But you’ll need to let the people mentioned in the will (or if there was no will, then those the state determines are entitled to inherit) know the deceased has passed and they have an inheritance coming. Make sure everyone involved in the estate knows when the probate hearing is.

Start the probate. There’s a slim chance you won’t have to go through probate, but most estates do. Generally, executors start this process around the two-to-three-month mark. Once it starts, you’ll get papers called letters that establish your authority to act on behalf of the estate—which you’ll need when you’re dealing with banks, utilities and businesses.

Inventory the estate. This probably won’t be fun, but you need to inventory the estate. That means taking stock of everything the deceased owned, including physical assets, as well as things you can’t store in the attic—like stocks. This also means identifying any debts owed, like mortgages or loans. Sometimes assets are hard to find. Depending on how large the estate is, it could take several months to find and claim everything.

Maintain the estate. While you take care of all those chores, you’ll also need to keep everything running. If the deceased owned a business, you’ll need to keep that running. You’ll need to maintain their house and keep paying utility bills, etc. It’s also your job to make sure the house or any other unoccupied property remains secure. And don’t forget about taxes, homeowners insurance and any mortgage.

Pick a real estate agent. While you’re waiting on probate for permission to sell the house, go ahead and interview real estate agents so you’re ready to go when the time comes.

Cancel life stuff. Cancel things like the decedent’s phone and internet service.

Notify Social Security. Let Social Security know the decedent has passed and return any checks received after the date of death, unless the decedent has a surviving spouse. If that’s the case, still let SS know, and they’ll direct the checks to the surviving spouse.

Notify others. Let any life insurance companies and account managers for IRAs, 401(k)s, etc., know the decedent has passed. Other institutions that might need to know: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Motor Vehicles, U.S. Postal Service, and Department of Veterans Affairs.

Get an EIN. Every estate needs an identifying number—kind of like people have Social Security numbers. In the case of estates, the government has declared they get an Employer Identification Number (EIN). Yeah, we don’t get it either. But you have to get one for the estate.

Open a bank account for the estate. You can’t go around writing checks for the deceased—that would be check fraud. So open a bank account just for doing business on behalf of the estate.

Notify the public. Place a notice of death in the local paper. This will let any creditors know the clock is ticking to get what they’re owed.

Add up the assets. You’ll need to figure out how much each asset is worth so you can divide it all up evenly or according to the will. You’ll also need to know this for taxes.

3–6 Months

The further out you get from the date of death, the more variation there is in what will still need doing. A lot of what you’ll need to do after three months is just a continuation of what you’ve been working on, like locating and maintaining assets.

Carry out a plan to distribute assets. Depending on how big the estate is, this could be a simple task or quite complicated. If it’s very complicated, you may want to hire a lawyer to help you. But either way, you need to come up with a plan for how the estate will be divided and given to any beneficiaries.

Sell the house or business. This would be part of the plan to distribute the assets. If there’s a house or a business that no one is inheriting, it will have to be sold and the proceeds divided among the beneficiaries.

Pay any debts. If the decedent owed any money, it’s your job to pay the creditors what’s owed out of the estate.

6–12 Months

Pay the taxes. That’s right. The taxpayer may be dead, but the government still isn’t going to let them rest until they’ve paid their taxes. But since they are dead, you’ll be doing it for them.

Depending on what time of year the decedent died, you may need to pay taxes earlier than six to 12 months out. (For example, if they died in January, you’d need to pay taxes in the first three months because federal income taxes are due in April.)

There are at least three types of taxes you’ll probably have to pay: the decedent’s personal income taxes, annual estate income taxes (yes, the estate becomes a “person” and “owes” income taxes once the owner dies), and annual property taxes (if they didn’t own a house or land, then you can nix this one).

Other taxes you may need to pay are estate and inheritance taxes. As of 2024, federal estate taxes only apply if the estate is worth $13.61 million—hey, good on the decedent for building that much wealth!1 Inheritance taxes are state level and only some states have them, so you’ll want to check with the state they lived in.

You may want to hire a good estate CPA to do the taxes for you. If you mess something up it can be a big headache.

Distribute the assets. You came up with a plan a few months ago and put it in motion—now it’s time to hand out inheritances to the beneficiaries.

Collect the executor’s compensation. You did a lot of work, and it can be a thankless job . . . but not totally thankless. Don’t forget to pay yourself out of the estate unless you’ve decided to waive payment.

Finalize probate. If the estate went through probate (it probably did), you’ll need to submit and get the court to approve a Final Accounting and a Final Statement. These documents lay out what you, as executor, did with everything in the estate, just to make sure it’s all aboveboard.

Final probate hearing. Schedule the final probate hearing to finish it all up and breathe again.

Grab Your Complete Guide to Estate Planning

Here's a sneak peek:

- Experts breaking down what you need

- Easy definitions for legal mumbo jumbo

- Education for every stage of planning

What Are the Main Issues That Come Up for Executors?

Sadly, we all know that a death followed by an estate process can be a tough time—for everyone. Emotions run high and can cause family fights and even legal issues. These are the main issues that can come up.

Disputes

As an executor, it’s your job to follow through on the decedent’s wishes as expressed in their will. Unfortunately, greedy or selfish relatives and even legitimate heirs may disagree with the way their loved one decided to divide the property.

It can help if you share the decedent’s specific wishes from the will with everyone, but that might not keep some relatives from arguing with you or even trespassing on the deceased’s property. That’s why it’s important to secure the estate’s assets and property as soon as possible.

Co-Executors

Are you sure you’re the only executor of estate for this will? News flash: Some wills name more than one executor. In many families, a parent will appoint two or more children as co-executors. That’s a fine sentiment, but it can also lead to needless arguments about who’s really in charge.

To avoid this problem, you have a few options. You could drop out of the process completely—after all, nobody is legally required to take on the role of executor of estate. But if it’s something you want to do, see if you can persuade the other co-executor(s) to drop out themselves. Or see if you can agree to pass the executor responsibilities on to a neutral third party like a bank.

Time Commitment

If you’ve read this far, you’ve probably started to see that an executor of estate has a ton of responsibility—and it can be a pretty big time sink. If you’re already swamped, look into getting professional help or asking the probate court for a replacement.

Personal Liability to Cover the Estate’s Taxes

This part feels a little scary, but you need to know the executor of estate can be held personally responsible to pay the deceased’s taxes. Now before you have a heart attack, it’s only under certain circumstances (aka if you pay the wrong people first and run out of money for taxes).

So, the order of paying people and institutions out from the estate is very important. For example, if you pay off debt or give beneficiaries their cut of the estate before paying taxes, and then you don’t have enough to cover taxes owed, that’s when the IRS can come after you for the money owed.

You’ll need to make payments from the estate in this order:

- Funeral expenses

- Estate admin expenses, like legal, court and executor fees

- Taxes

- Creditors

- Beneficiaries

Now, remember there are a few tax categories you’ll have to consider and you may have to file these at separate times. Usually, the final estate taxes can’t be paid immediately, so you’ll need to carve out an estimated amount for those from the value of the estate before you move forward paying everyone else.

By the way, the IRS can keep going after an estate to get taxes owed for 10 years, so make sure you set aside the money and get all taxes paid.2

If an estate doesn’t have enough of the green stuff to pay even the taxes in the right order, the executor needs to petition the court to get the estate declared insolvent. Basically, the court says the estate is bankrupt. In this case, you won’t be held responsible for any taxes (or debts).

If you’re considering putting on the executor hat, it’s a good idea to make sure you’re aware of how much the estate owes compared to how much it’s worth so you know what you’re getting into.

Do Executors Get Paid?

Fo sho. With all the responsibilities, liabilities and time drains they have to endure, executor of estate might be the worst job in the world if it was unpaid. Executors are paid out of the estate. How much they get paid varies—sometimes it’s a percentage of the estate, a flat fee, or even commission on transactions they have to make while settling the estate (think selling the house).

If they choose, executors can decline getting paid. Like we mentioned earlier, this can happen when the executor is also a beneficiary and they don’t want to reduce the total value of the estate or pay taxes on their compensation.

Interested in learning more about estate planning?

Sign up to receive helpful guidance and tools.

How Do You Choose Your Executor of Estate?

Maybe you’re on the other side of things and looking to name an executor in your will. Unless you have an accountant or estate lawyer for a daughter-in-law, you might be scratching your head on who to pick for your executor.

Your decision will depend on a few things, including how big your estate is, what your family and close friends are like, and how they get along. The job of executor isn’t for the faint of heart or anyone who doesn’t handle numbers and finances well.

Earlier, we mentioned that being an executor means you have a fiduciary duty to fulfill. The word fiduciary comes from the Latin word for trust—and being a good executor of estate is all about being trustworthy!

Let’s look at some things to consider when picking your executor of estate.

Personal Qualities

Think of someone you know (family member? friend?) who’s shown that they’re trustworthy, conscientious, and good at talking with people. Does anyone immediately come to mind? If so, you’re already off to a great start.

Keep in mind that the person you’re considering also needs to be mature. Of course, we all have our moments of silliness, but in general, does this person handle life events with a level head and an honest heart?

Location

You need to think about where your potential executor lives. Here’s why. They end up spending a good chunk of time working with the courts in your area.

Is this a deal breaker? Not necessarily. If you already have someone in mind who has all the right personal qualities but lives out of state, research your state’s requirements for executor location. Who knows? Virtual meetings might be perfectly acceptable. Do some digging.

Time Commitment

Here’s something else to think about. The amount of time needed for an executor to handle your affairs when you’re gone could be enormous. We’re not talking about 10 minutes here and there. Depending on the complexity of your estate, it could take months or even years. Does the person you have in mind have enough free time to make that kind of time commitment?

We’re all busy, yes, but some of us are busier than others (single parents with small kids immediately come to mind). Think hard about whether or not they have the bandwidth to take on a new responsibility.

Finally, once you settle on a suitable candidate, be honest with them about what you’re asking. And try to remember that they do have the option to say no. Worse case? If you’re unable to find someone appropriate, you can always hire an outside professional executor.

Here are a few more practical qualities to look for:

- Responsible: They’ll have to know how to meet deadlines and deal with a judge.

- Experienced with finances: They don’t have to be an accountant, but they need to be comfortable dealing with financial institutions and numbers.

- Financially secure: Their finances are in order. They don’t have a ton of creditors, never declared bankruptcy, etc.

- 18 years or older

- No criminal record

- U.S. citizen

- Mentally sound

It’s common for a testator (again, that’s the person writing a will) to name their spouse as the executor of estate. But it’s often another family member or close friend. And it can even be one of the beneficiaries of the estate itself.

As with beneficiaries, it’s a good idea to name a backup executor in your will as well. Because your will could be quite old by the time it’s used, this guy or gal should be younger than you and in good health.

For larger or more complex estates, it might make sense to name a professional third party, like a bank or trust company, as your executor to head off any legal headaches for your beneficiaries.

Remember, if you’re choosing someone to act as executor for your own will, be sure they’re a person of integrity who will see the whole thing through even if it gets complicated.

Wouldn’t you rather have a clear plan in place for your own executor of estate, instead of leaving these questions for some probate court to decide? Of course!

Here's A Tip

Whether you’re simply shopping for a will and wondering who to appoint as your own executor of estate or taking on that role yourself, you need a will and a way to organize your estate. And if you didn’t see that before, taking on executor responsibilities will convince you!

You can create your own will online with RamseyTrusted provider Mama Bear Legal Forms in less than 20 minutes! They provide attorney-built documents that are state-specific and legally binding. All you need to do is plug in a few answers, and the rest of the work is done for you. Once you’ve purchased, there’s no rush. You have 180 days to complete the form from there.

That’s one of the things B. Smith loved about setting up his will through Mama Bear.

“It was very easy, and they give you six months free to make changes,” he said on the Ramsey Baby Steps Facebook Community group. “You’d be surprised all the stuff you forget and then think about later. That 6 months was GOLD to me. I kept thinking of other stuff.”

Once you’ve made your will, put a copy in your legacy drawer—along with copies of all your other important documents like tax returns and investment statements—so your executor and family can access it when the time comes.

Organizing your estate is a key step in financial planning and in loving your family well.

Next Steps

- Learn more about how to administer an estate.

- If you don't have a will, read about why you need to get one ASAP.

- Take our quiz to find out if an online will is right for you.

- Complete this worksheet to make sure you have all the info you'll need to create your will.

- Start your will with RamseyTrusted provider Mama Bear Legal Forms.

Complete Last Will Package for Married Couples

Complete Last Will Package for Individuals

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Does a court need to approve the executor of estate?

-

When an executor of estate is named in a will, a judge must approve the person named. There are several reasons why a person named by a will to be executor could be disqualified, including a criminal record or being underage.

-

Do executors of estate get paid?

-

After all the fees and taxes have been taken care of, executors get paid out of the estate. If the will stated a number for their pay, they’ll get that. Otherwise, state law will decide how much the executor gets paid—usually a percentage of the estate. It’s a complicated job that takes a lot of time, so it’s a good thing these people get compensated!

-

Can an executor of estate also be a beneficiary?

-

An executor is often also a beneficiary—parents often name one of their kids, for example. This works well when family dynamics are healthy but could lead to accusations of unfairness and fighting if the beneficiaries involved don’t get along or are unhappy about the choice. If you’re thinking about who to name as an executor in your will and your family isn’t the most harmonious unit around, consider naming a neutral party like a bank to execute the estate.

-

Can an executor override a beneficiary?

-

Even if an executor doesn’t like a beneficiary or doesn’t think they deserve what’s left to them, they can’t deny a beneficiary their inheritance as named in the will. But if a beneficiary disagrees with the executor on something the will says to do, the executor can override the beneficiary’s opinion or desires. As long as the executor is doing what the will or a judge says and serving the estate, they have authority.

-

Is an executor of estate the same as a trustee?

-

While both an executor and trustee deal with estates, make sure beneficiaries get their inheritances, and pay taxes and debts, they’re very different roles.

An executor of estate deals with an estate after the owner is deceased. A trustee takes care of a trust as long as the trust is in existence—which can be during the life of the trust creator and/or after they are deceased. Trusts can last a very long time, so a trustee’s responsibilities are usually a lot bigger than an executor’s.